Businessweek.com mention the name Google (Gphone) in cell-phone software circles these days and you’re likely to get a lot of blank stares and awkward silence. It’s not that these Silicon Valley startups have nothing to say about the world’s largest Web search engine. The problem is, they can’t. Many mobile-software developers in the Bay Area and beyond are hard at work cobbling together services and tools they hope will be packaged with a wireless operating system under wraps at Googleplex—and they’ve been sworn to secrecy.

Word’s getting out. Among the companies jockeying for a place on Google’s platform, BusinessWeek.com has learned, are Plusmo, a Santa Clara (Calif.) company that pulls together blogs and news items and sends them to cell phones, and Nuance Communications (NUAN), a Burlington (Mass.) maker of speech-recognition software used in mobile directory assistance services. Plusmo is owned by Reify Software, and its services are already available on phones made by Motorola (MOT), Research In Motion (RIM), and devices that use the Microsoft (MSFT) mobile operating system. Nuance technology, on devices such as Palm’s (PALM) Treo 755p, lets users dial, dictate, and search using voice commands. Neither company would comment for this story.

Code Unlocked

Another startup said to be working with Google is 3Jam, a software maker in Menlo Park, Calif., that lets users send text messages to groups of friends. Representatives of 3Jam declined to comment.

Google also is mum on its plans, but the ongoing work with developers may give further evidence the company is moving ahead with a platform, possibly named gPhone, that brings together a range of services—from news to instant messaging to social-networking features to Web browsing—for mobile phones. “If they are evangelizing to mobile developers, they probably have a product coming soon,” says Toni Schneider, chief executive of Web publisher Automattic, who created Yahoo!’s (YHOO) developer program. For developers, the Google platform could open a wide range of opportunities, including changing the way programmers use and build Google applications for mobile devices. And the interplay between Google and software developers is likely to leave an indelible mark on how wireless services are built and distributed—and who gets to share in the spoils.

Google’s platform is expected to consist of an operating system, mobile versions of Google’s existing software, and built-in tools that make it easier for developers to dive in. Google is expected to open up much of its gPhone programming code, known in industry parlance as the application programming interface (API), enabling mobile developers to easily integrate Google’s applications with their own software and to distribute those applications to all users of the gPhone platform (BusinessWeek.com, 9/6/07), whatever phone model or carrier they happen to use.

Cooler Apps

The idea of unlocking software code to outside developers is gathering currency across the tech landscape. Case in point: Thousands of companies have embedded Google Maps into their Web sites to help customers and clients find offices. At the same time, Google offers a range of third-party applications, such as the online encyclopedia Wikipedia, on its customizable home page iGoogle.

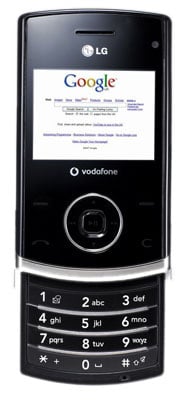

Still, that same cross-pollination has yet to take off in wireless circles, where carriers and handset makers control which applications are available to users. Earlier this year, Google had to strike a special agreement with handset manufacturer LG to get its YouTube video application onto an upcoming mobile device. Carrier AT&T (T) and handset maker Apple (AAPL) handpicked the Google applications—Google Maps, search, and YouTube—that would be available on the iPhone, introduced in June.

The relatively closed system gives service providers and cell-phone manufacturers tight control over what users get—and pay for—on their handsets, but it keeps the makers of cool applications on the sidelines. On a typical smartphone running the Symbian operating system, fewer than 40% of the applications came from third-party developers, according to Symbian data.

Not only would the Google model mean more cool new apps and open sales avenues for developers, but it’s also likely to influence how the industry deals with other mobile operating systems. Says Thomas Howe, head of communications software consultancy the Thomas Howe Co.: “The world will break open.”

More Ad Revenue

Since talk of the gPhone emerged, developers whisper that other companies, including Apple, may open their mobile-software platforms to programmers. “Mobile platforms will become very common in the next year,” believes developer Craig Hockenberry. “We are on the cusp of a major shift in mobile technology.”

Part of that shift will involve greater organization on the part of open-source developers creating applications in mobile Linux, which comes in many different flavors. “There are a lot of fragmented initiatives,” says Jerry Panagrossi, vice-president of U.S. operations at Symbian. “A developer has to overhaul their code for every application they target.” By designing for gPhone’s particular flavor of Linux, open-source developers may be able to present a unified front—and reduce development costs. Consultancy ABI Research forecasts that Linux will be the fastest-growing smartphone operating system in the next five years. “Google has a lot of muscle to distribute things and to get [developers] excited,” says Automattic’s Schneider.

Part of that excitement stems from the possibility for developers to tap a new revenue source: mobile advertising, instead of user subscription fees. Developers may be able to share in revenues from ads displayed in the applications. Three weeks ago, Handmark, which sells applications and content for personal digital assistants, began displaying banner and search ads in its applications. It’s seeing a 9% click-through rate on its display ads and a 10% conversion rate on users who use the click-to-call service from its local paid-search feature. By contrast, PC Web banner ads often generate click-through rates of less than 1%.

“Openness would pay off for everybody,” says Mike Phillips, co-founder of vlingo, a maker of software that lets users type using voice. Google’s lips are sealed, but the buzz among mobile developers is well under way. Says John SanGiovanni, co-founder of ZenZui, a maker of tools used by mobile-widget makers. “We certainly hope Google will give us an honest-to-goodness mobile platform, so that we can party on it.”

The story talks about a handful of Boston entrepreneurs and venture capitalists who have seen the phone, but are under NDA and can’t talk about it. Rich Miner, a co-founder of Android, a mobile software company he started with Andy Rubin (formerly of Danger)

The story talks about a handful of Boston entrepreneurs and venture capitalists who have seen the phone, but are under NDA and can’t talk about it. Rich Miner, a co-founder of Android, a mobile software company he started with Andy Rubin (formerly of Danger)